The Central Otago Gold Story

Adventurers, Prospectors, Pioneers - The Gold seekers ventured into an untamed land of desolate mountains, swift rivers and an unforgiving climate.

Over the next hundred years, their changing fortunes transformed Central Otago as towns took root, business boomed and sometimes bust, and the landscape was reshaped as miners dug ever deeper to find the prize. We’ll never know exactly how much was won. What is certain is that the gold seekers paved the way to the region we know today – a place rich in history, pioneer spirit and strong communities.

Like the stars in Orion on a dark frosty night.

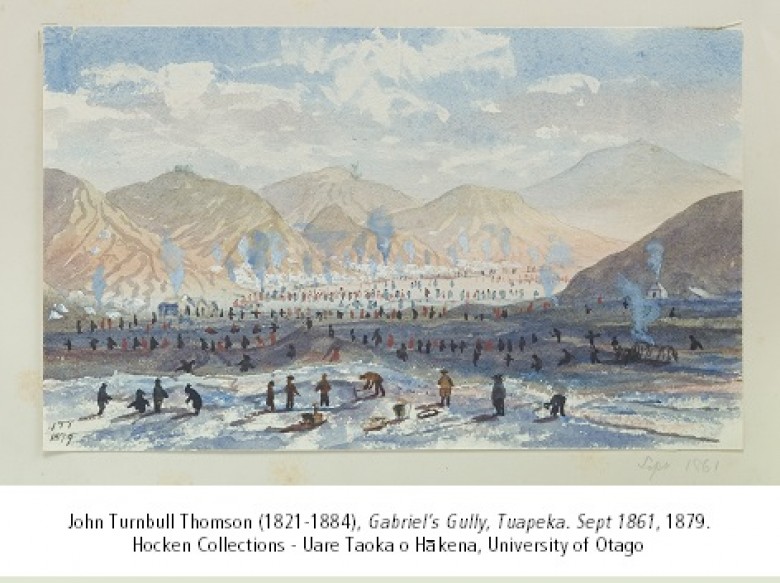

In the early 1860s Otago was a young pastoral province. Half a million sheep nibbled its tussock country while Dunedin flourished off the back of wool exports. The arrival of a young Australian prospector would change the face of Otago forever. His name was Gabriel Read, and in 1861 he made the long journey to Tuapeka (modern-day Lawrence) carrying little more than a tin dish, pick and shovel. Read found gold as soon as he arrived, shining in the gravel ‘like the stars in Orion on a dark frosty night’.

As word of his discovery spread, thousands of prospectors flooded in, most via the Californian and Victorian rushes that were petering out by then. Many were originally from the British Isles, while others came from America or Europe. What most had in common was enough money to pay for their passage to New Zealand, and the strength of spirit to try their luck in a faraway land. But money and pluck would only get them so far.

It was winter when the first wave of hopefuls headed to Tuapeka. Despite rugged terrain, unformed tracks and freezing conditions, 14,000 diggers had arrived by Christmas 1861. But as the easy finds were worked out, men started drifting away almost as quickly as they came. Within months, the Otago gold rush was reignited when Californians Horatio Hartley and Christopher Reilly deposited a whopping 32kg of gold at the receiver’s office in Dunedin, sewn up in scraps of their trousers. They’d panned it from the Dunstan Gorge on the banks of the Molyneux – the river we now call the Clutha Mata-au. In the following years vast quantities of gold would be recovered from the river and its tributaries.

There was no time to dilly-dally.

First, prospectors had to stock up on provisions and gear, likely to have included the standard diggers uniform of a blue serge shirt, moleskin pants and a ‘Billy-cock’ hat. While getting to Tuapeka had proven hard, the journey to Dunstan was even more arduous, leading the diggers even further into the Otago’s inhospitable hinterland. Those lucky enough to own a horse could gallop from Dunedin to the diggings in a couple of days flat, but most trudged to the goldfields on foot with up to 40kg of swag on their backs.

Such was the hurry that many men took the infamous mountain track, now known as the Dunstan Trail. Although the shortest route, it was also the most treacherous with a 50km section crossing the desolate tops of Rough Ridge and a highpoint of 1000m. Some never made it, turning back at the point of exhaustion or even perishing en route. But in the words of a local storyteller, ‘Nothing is impossible when it is a matter of reaching gold.’

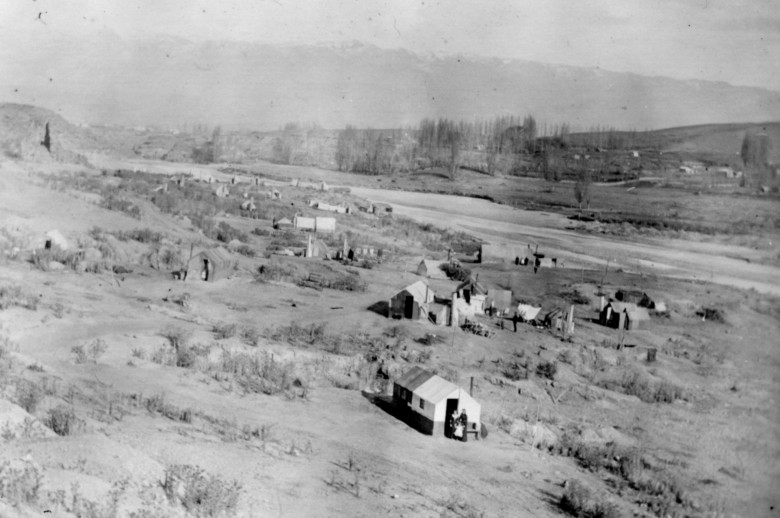

Within weeks, tents and shanties lined both sides of the Molyneux for 70 miles from modern-day Cromwell to Beaumont.

The newcomers faced a tough life on the goldfields. Even those who’d come via California or Victoria found the Otago hinterland much wilder and more rugged than any place they’d ever been. It was desolate and treeless, with brutal mountain ranges and unforgiving rivers. The winters were Arctic, the summers scorching with little shade to provide relief.

Arriving hungry, many of the men converged on Earnscleugh Station, named Mutton Town for the meat sold at a shilling per pound. The station’s boat was also used for crossing the Molyneux, saving the diggers a dangerous swim.

The rip-roaring towns of the Junction (Cromwell), Upper Dunstan (Clyde) and Lower Dunstan (Alexandra) soon sprung up, slung together from whatever materials were on hand. Calico, sod, stone, mud-brick and tin were all used, as were tussock and scrub. Some diggers built rock bivvies, while luckier ones got hold of precious timber, rafted downriver from Wanaka.

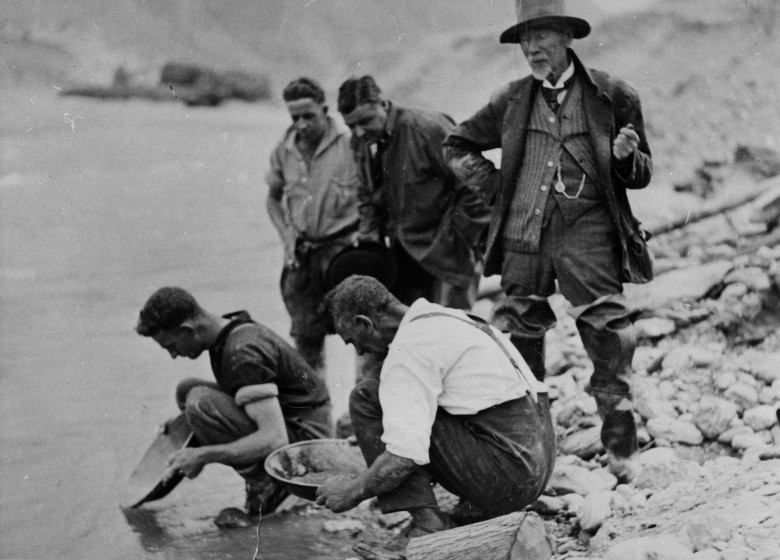

Out on the riverbanks, it was pretty easy to get gold

Hole by hole, they dug up ‘wash-dirt’

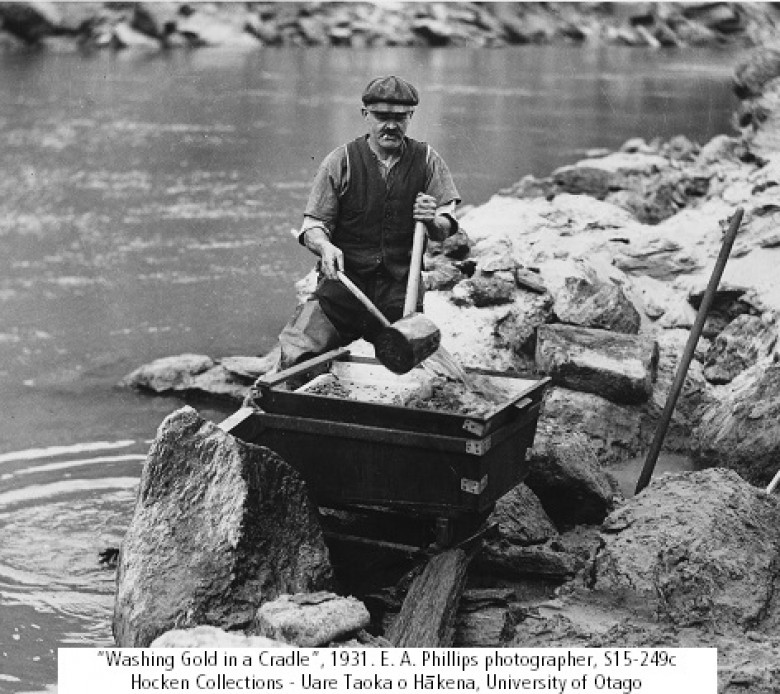

Diggers pegged out a claim of around 80 square metres, known as a paddock. Hole by hole, they dug up ‘wash-dirt’ and panned it in their tin dishes to reveal anything from a few specks to flat, wee nuggets the size of a small coin. Some men also used a wooden cradle, known as a rocker box. The wash-dirt was shoveled in and rocked, trapping the gold in a series of slats.

At the end of a hard day’s work, the men would return to their dwellings. In winter these were so cold that one fellow claimed he had to defrost his boots and clothes under the blankets before he could put them on in the morning. A typical meal was chewy muttonchops and damper, washed down with rough black tea. Storekeepers ‘grubstaked’ the diggers, extending credit until they panned enough gold to pay their way. Between a captive audience and inflated prices the storekeepers thrived, with one butcher reporting that he ‘made money fast … and fitted up a comfortable home for my family.’

Social life revolved mostly around grog shanties or hotels where the diggers drank, smoked, gambled and caught up on news. There were more than 20 hotels on the goldfields by 1863, and competition was fierce. Elaborately dressed dancers and barmaids, billiard tables and concert evenings enticed the punters in.

The diggers were quite a musical bunch, with the goldfields ballads of Charles Thatcher striking a particular chord with Otago’s miners.

Goldfields Ballads

Old the diggings we’re all on a level, you know:

The poor man out here ain’t oppressed by the rich

But, dressed in blue shirts, you can’t tell which is which

Charles Thatcher

There were few women around. The first arrivals were mostly single women, drawn for much the same reasons as the menfolk – the chance to earn a decent living and settle down. While some worked as sly-grog sellers, barmaids and prostitutes, they were just as likely to be cooks, bakers, washerwomen and seamstresses. An intrepid few also worked on the diggings. Most spinsters were ‘wed in a jiffy’, and joined the ever-growing ranks of married women with children in tow. The hardships of life on the goldfields meant that many were widowed early.

In 1864, the Otago Gold rush was at its peak

An estimated 40,000 diggers worked claims from Kyeburn to the Kawarau. Among many new towns were Hogburn (Naseby), Blacks (Ophir) and Oturehua where many relics of the gold days can still be found today.

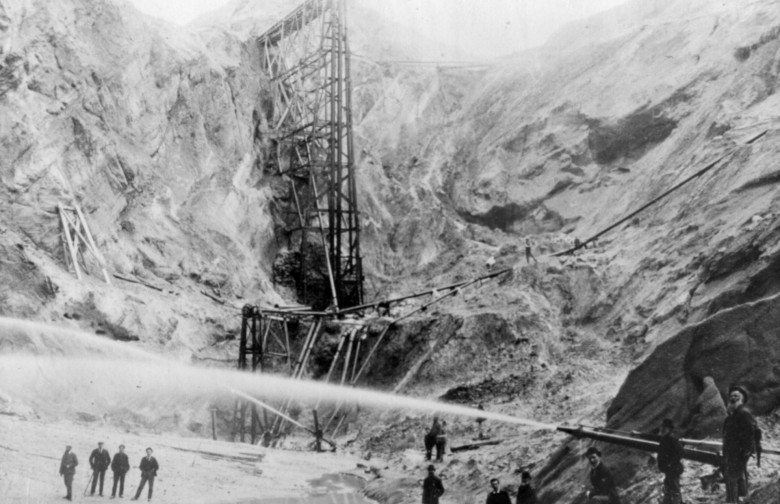

As the easily won gold from the riverbanks started to run out, the prospectors moved up to the terraces and gullies where high-pressure water cannons were used to pound rock faces into washable gravel. Called hydraulic sluicing, this mining method changed many Otago places beyond recognition. A classic example is Bannockburn Sluicings, a stark and strange landscape of tailings, caves and tunnels that blurs the lines between man-made landscapes and the natural world.

In 1864 quartz mining cranked into action, in which schist was blasted, crushed and mixed with mercury or cyanide to release the fine gold. The impressive stamper batteries and other rusty relics of this era await discovery in remote, surprising places, such as the Come in Time Battery near Bendigo.

Both hydraulic sluicing and quartz mining used masses of water, triggering the frenzied construction of water races that tapped, re-routed and dammed countless streams. Built from stone, timber and sheet iron, races stretched up to 80km long. Many can still be seen snaking around the hillsides. As gold mining became more mechanical, the diggers deserted Otago in their thousands. Alarmed by flagging revenues, Dunedin’s Chamber of Commerce invited Chinese miners to give the old diggings another going over.

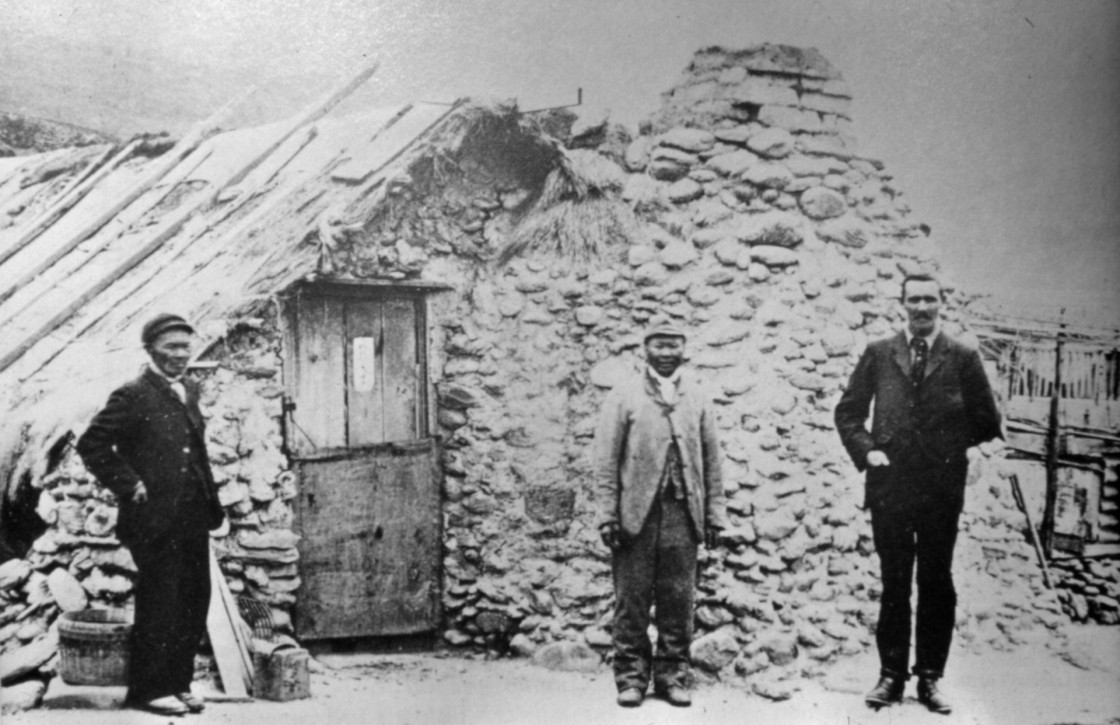

Arriving via the Victoria goldfields in a trickle from 1865, the Chinese numbered more than 2000 by 1870. They proved clever and hardworking. Chinatowns, skilfully crafted from rock and other salvaged materials, were a hive of industry complete with stores, boarding and eating houses, gambling and opium dens. Year after year they laboured on, their stories rife with prejudice and personal suffering.

While many of the Chinese returned to their homeland, others stayed on to work on sheep stations or establish laundries and other businesses. They proved particularly skilled at market gardening, which improved the health of local people as fruit and vegetables were easier to get.

Goldfields proved fatal all too often

Between the merciless climate, rugged terrain and treacherous work, the goldfields proved fatal all too often. Local cemeteries bear witness to such fates as drowning, rockfall, hypothermia, disease, malnutrition and even murder.

Digging Deeper to reach their prize

From the late 1870s, the hydraulic elevator helped keep gold fever alive. It enabled miners to sluice to greater depths by sucking the wash out of the paddock via a pipe and delivering it into sluice boxes above the mine. This had a truly dramatic effect on the landscape, as evident at St Bathans. The peculiar Blue Lake there was once Kildare Hill, 120 metres high. Sluiced flat, the elevator helped excavate a massive, 70-metre ‘glory hole’ – the deepest gold claim in the world back then.

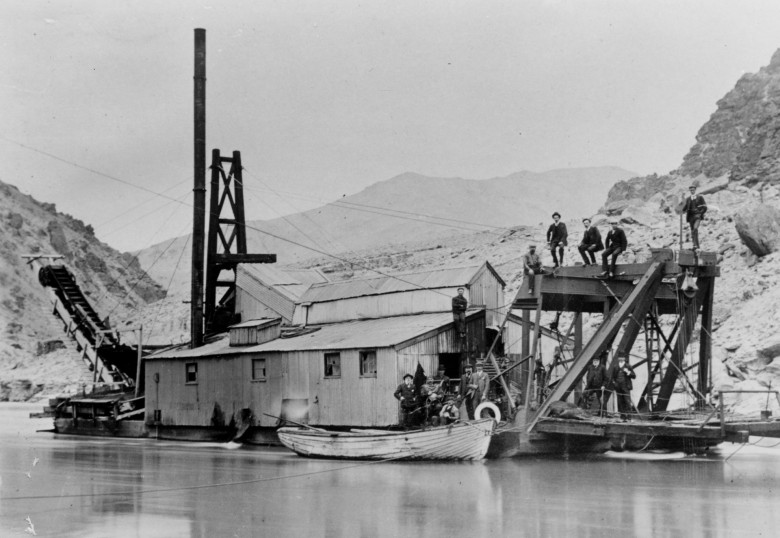

The biggest revolution in gold mining, however, was the gold dredge that turned both the industry and the riverbeds on their heads. From the early days of the gold rushes, simple dredges had been used to scoop up river shingle for panning or sluicing. In the early 1890s, however, the invention of a new dredge triggered a boom on the Clutha and its tributaries. Locally designed and engineered, the steam-driven ‘Standard’ or ‘New Zealand’ dredge was copied as far away as Siberia and made Alexandra the gold dredging capital of the world.

By the turn of the century the boom was at its peak. The Clutha and Manuherikia Rivers were being worked by dozens of dredges, kept cranking 24 hours a day, six days a week by crews of up to ten men. Each dredge burned up to five tonnes of coal per day. Getting the coal on board was difficult, dangerous and expensive, so companies began experimenting with hydropower. You don’t have to look far to see the effect this new industry had on the Clutha Mata-au River. Not only would hydro lakes and dams change the landscape forever, they flooded the old Junction town and many of the diggings where the old-timers had toiled.

As the gold in the rivers ran out, some dredges were adapted to work in ponds along the riverbanks. As they chewed through productive agricultural land and the tailings piled up, trouble brewed between mining companies and local communities. A correspondent to Alexandra’s Evening Star summed up the conflict when they wrote, ‘… in a district like this, where fruit-growing is more precious than mining land, it is a thousand pities to see a corner that would keep a family in comfort for all time … destroyed for the sake of the gold that lies on the bottom. It is a veritable outstanding example of killing the goose that lays the golden egg.’

In the end, though, it was a lack of gold that finally brought the dredging era to its close, with the giant Clutha grinding to a halt at Earnscleugh in 1962.

Nearly 60 years on, wild flowers have taken root amongst the tailings. At first glance, these barren mounds of gravel may appear like a strange creation of nature. But look again. Like many places in Central Otago, the landscape reveals its secrets in curiously straight lines, neatly stacked rock, relics hidden in the midst.

Shaping Central Otago

The people who stayed on after the gold rushes played a major part in shaping Central Otago.

The roots of our thriving wine industry can be traced back to digger John Desiré Feraud, the Frenchman who planted the region’s first grapes near Clyde in 1864. For the famously delicious Dawson cherry, we can thank miner’s wife Mrs Dawson who planted fruit trees after a storekeeper sold her some on the cheap. By the 1870s, the Dawsons had teamed up with their neighbour to establish one of the region’s pioneering orchards, on land reclaimed from old diggings.

Many more miners turned to working the land as it came up for purchase or lease. The water races once used for sluicing were now used for irrigation, turning the landscape greener with every passing year. As communities bedded down, so did town councils and civil works such as building a hospital and planting parklands. New roads and bridges made journeys safer and easier, and helped the young province grow even more.

Patient, persistent and thorough

Stu Edgecumbe still keeps his hand in, but he’s not looking to strike it rich. The former postmaster’s passion is teaching gold panning on his Roxburgh claim – down the back of his house where a garden shed serves as a mini-museum. ‘It’s the most satisfying job I’ve ever had,’ says Stu. ‘My visitors love being in nature, the movement of water. It teaches them to be patient, persistent and thorough – and reap reward from their effort.’

Des Styles has also done his bit to keep gold mining history alive, his short stories and poetry recalling old friends and old ways, and his countless years spent prospecting up the Kyeburn. Did he find much? ‘A few bob,’ says Des. ‘But you spend so much time looking for it, it’s not worth breaking your back.’

Back in the day, there wasn’t much choice, with Stan Murray’s father typical of the hard-grafting miners of the time: ‘He worked eight hours a day, six days a week, and three days off each year. The weights he lifted, the loads he carried, the sledgehammers he wielded … mining called for a measure of human slogging which is almost impossible for us to imagine.’

Reminders of what went before

With their sweet briar, wild thyme and bright orange poppies, places like St Bathans, Bannnockburn and Earnscleugh are not without beauty. But what landforms, plants and creatures were lost as the gold was mined? The water races snaking around Central Otago hillsides are other reminders. Without them, the fruit-growing industry may have never flourished in this once bleak, desolate place.

The patchwork of pretty orchards, gardens, parks and forests planted over the last 160 years has transformed ‘dusty Dunstan’ into an all-seasons fiesta of colour and flavour. Communities have also taken root, carrying down the generations a stoic determination and resilience, along with the stories that breathe life into the landscape and remind us what went before.

Scratch the surface and an old gold story may lie underneath

OUR REGIONAL VALUES

Make a Difference

Be at the cutting edge, setting directions and accepting challenges.

Respecting Others

Take the time to listen and understand other people’s opinions and cultural differences.

Embracing Diversity

Be open to new ideas, open to exploring the possibilities and appreciate the strengths and talents each person brings.

Adding Value

Always ask ourselves is there a better way – one that achieves a premium status, quality experience or interaction.

Having Integrity

Seek to be open and honest in all our interactions.

Learning from the past

Choose to learn from past experiences with the future generations in mind.

Making a sustainable difference

Make decisions with the community in mind and in harmony with the natural environment so we can help create the kind of place we can be proud of.

Protecting our rich heritage

Protect and celebrate our rich heritage in landscapes, architecture, flora, fauna and cultural heritage.

Meeting our obligations

Do the right thing by our region and check what legal requirements need to be met before you get started.

Related Stories

-

Central Otago Cycling Story

Our landscapes, places, people and climate have created a bikers' paradise for every age and stage

Read more about Central Otago Cycling Story -

The Teviot Valley Story

This is the Teviot—a diverse and special place, endowed with nature’s goodness and dynamic, strong communities. Here the land gives generously and the people do too.

Read more about The Teviot Valley Story -

The Cromwell Story

Today, New Zealand’s farthest inland town has a new, uplifting energy as people are attracted to the Cromwell Basin’s sunny, dry climate, and the work and lifestyle opportunities. Now over 20 years on from its beginnings, Lake Dunstan has become the jewel in the Cromwell Basin’s crown - a glistening, inviting adventure playground.

Read more about The Cromwell Story -

Manuherikia & Ida Valley Story

The Manuherikia and Ida Valleys are proud, timeless places. Edged by sturdy mountain ranges and crumpled velvet hills, they are soul country.

Read more about Manuherikia & Ida Valley Story